Martin Seligman

Martin Seligman is the father figure of positive psychology, but his early research was a bit less positive. He was looking at the concept of helplessness. What he did was create particular situations of helplessness, e.g. dogs got electric shocks that they could not escape from. There was nothing they could do to get away from the shocks. After a certain amount of time, most dogs just gave up trying. They became helpless or learned to be helpless.

Another researcher, Donald Hiroto, found that the same thing happened with people. With people, they didn’t use electric shocks (there have to be some limits). The researchers used inescapable noise (remind you of early parenthood?). And when people worked out that nothing they did could get rid of the noise, they just stopped trying.

But the really interesting thing with both the dogs and the people was that some didn’t give up. Some kept on trying despite their efforts seeming not to work. Why? What was different about this group that stopped them from learning to be helpless? The model Seligman and others proposed for this was based on what they called “your explanatory style”.

But the really interesting thing with both the dogs and the people was that some didn’t give up. Some kept on trying despite their efforts seeming not to work. Why? What was different about this group that stopped them from learning to be helpless? The model Seligman and others proposed for this was based on what they called “your explanatory style”.

This is your way of making sense of bad events, and Seligman said your explanatory style “is a habit of thought learned in childhood and adolescence”. At its simplest, there are two extremes of explanatory style, pessimism and optimism.

In the pessimistic explanatory style, bad events are:

Permanent—the bad things are going to last for a long time, things are not going to get better.

Permanent—the bad things are going to last for a long time, things are not going to get better.

The project I’m working on is not going well and it’s not going to get any better.

Pervasive—one bad thing affects everything. This is called being universal. One bad teacher means all teachers are bad. A bit like a bad smell, bad things spread around.

If this project fails it will affect my chances of getting a promotion, maybe my whole career.

Personalised—pessimists take bad things personally. They blame themselves. They take internal responsibility.

The project is going badly and it is all my fault. I should have been able to fix it.

In the optimistic explanatory style, bad events are:

Temporary—this is just one slip up. This will go away or change after a while.

Temporary—this is just one slip up. This will go away or change after a while.

The project is having a bit of a setback but I’m sure things will pick up.

Specific—this is a once off. The bad thing doesn’t spread around and affect other stuff.

Even though this project isn’t doing so well, others are going great. And even if this project doesn’t work out, it will be over soon and I’ll move on to better things.

Externalised—something else out there, something external, was responsible for this bad stuff.

The dog ate my homework. I did my best, we just didn’t have the right people on the team, it was the wrong time, the economy was bad at the time.

“The defining characteristic of pessimists is that they tend to believe bad events will last a long time, will undermine everything they do and are their own fault. The optimists, who are confronted with the same hard knocks of this world, think about misfortune in the opposite way. They tend to believe that defeat is just a temporary setback, that its causes are confined to just one case. The optimists believe that defeat is not their fault.”

Martin Seligman, (1991), Learned Optimism, page 4

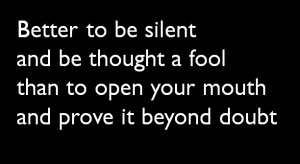

At this point those among you who might be called pessimists (you probably prefer the term realist) will be thinking—but you can’t just go around with your rose tinted glasses thinking everything is rather jolly when the reality shows you sometimes things are not rosy at all. And of course you are right.

However, the problem for the pessimists, sorry, realists, is that regardless of whether they are right or wrong, they feel worse than optimists. Pessimists are much more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety. Optimists might be wrong sometimes but despite this, optimism is better for your mental health. And of course this can become self-fulfilling. Once you feel better you are more likely to perform better. And things will probably turn out better. All rosy.

So how does this relate to the imposter syndrome? Well, as you can imagine for pessimists, failure or mistakes are bad. Very bad. They are going to last forever, mess up everything else and they’re your fault too. So you don’t want to be making mistakes. That’s how you will be exposed.

Yet the difficulty is that you will make mistakes. We all make mistakes. So the imposter’s dilemma is, “I have this image that I need to be really good and get it all right. Yet I make mistakes. So I must be a fraud, right?”

The optimist explanatory style is a bit kinder. I made a mistake. Yeah we all make mistakes. It’s just this once. And it doesn’t affect other stuff and it was somebody else’s fault anyway. Let’s move on.

Extract from The Imposter Syndrome by Hugh Kearns.